Tales of ghosts haunt Demopolis landmarks, river

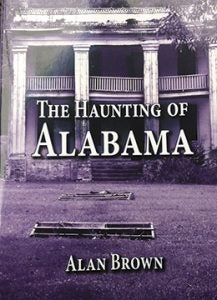

Stories of ghosts and ghouls thrive during Halloween, and Demopolis has its fair share of them. Dr. Alan Brown, a professor at the University of West Alabama and author of nearly 30 books on southern ghosts, shared three stories featuring local haunts from his latest book, “The Haunting of Alabama.”

Bluff Hall

Bluff Hall, built in 1832 and purchased by the Marengo County Historical Society in 1967, has had a number of owners.

In his book, Brown interviewed one woman who decided to see if the ghost stories surrounding the property were true. In 2003, on the night before Halloween, the woman took her daughter and her daughter’s friend to spend the night.

As night approached, Brown said they heard what sounded like “a girl jumping rope.” Later that night, after her daughter and the friend were asleep, the woman decided to investigate on her own, and she confirmed for herself the ghostly reputation of Bluff Hall.

“She looked down and saw a little boy standing next to her,” Brown said.

He went on to say that the woman told him she was concerned, rather than afraid, because the young boy seemed to be searching for something.

She went downstairs and sat down, only to see the young boy out of the corner of her eye again. This time, he was staring out of a window.

Brown explained that the little boy was the grandson of the original owners, Francis Strother Lyon and his wife Sarah. The boy contracted scarlet fever while visiting his grandparents while his mother stayed in New York to give birth. During his illness, the little boy kept hoping for his mother to come see him, but she didn’t make it in time.

“Apparently that little boy’s ghost hangs around looking for his mother,” Brown said, adding “It’s a very sad little story.”

Gaineswood Mansion

“Gaineswood’s ghost is more famous,” Brown said, citing Kathryn Tucker Windham featuring it in her book, “13 Ghosts of Alabama and Jeffrey,” as the reason.

Gaineswood Mansion was built by General Bryan Whitfield, whose wife died before construction was complete in the mid-1800s. Needing someone to help care for his children, Whitfield hired a nanny, known only as Miss Carter, from Virginia.

Living so far away from her family, Carter became depressed, so Whitfield invited her sister Evelyn Carter to live with them.

“She lived there a few months, and then she died, and no one knows how she died,” Brown said.

One proposed theory, he mentioned, was that Evelyn fell in love with a French Count, but the relationship ended after a particularly heated argument. Evelyn is said to have died of a broken heart.

Evelyn wanted to be buried in her home state of Virginia, but she died during winter, and the roads were impassable. Brown said that Whitfield stored her coffin in the cellar until she could be moved.

“Well, a few days later, members of the Whitfield household complained of footsteps going down to the cellar,” Brown said.

He also said that the piano could be heard when no one was playing it, a haunting detail that remains today.

After interviewing two workers at Gaineswood, Brown heard the real story. Whitfield hired a teacher named Elizabeth Robertson, who later became ill and died. Her coffin was stored in the Glover Mausoleum before being transported to her home in New York.

“So you can see how the folktale was generated by the facts,” Brown said.

Today, the sweet smell of gardenias has been reported numerous times, which is thought to be Elizabeth welcoming visitors to the home.

Eliza Battle Steamboat

Though the ghost of the Eliza Battle Steamboat is shared along the Tombigbee River, the spectral vessel has its ties to Demopolis.

The steamboat transported cotton from Mobile to Warsaw, Alabama and multiple towns in between. Often, farmers and their families would accompany the cotton and enjoy some off-time on the steamboat. This led to the company behind the Eliza Battle to advertise the vessel as a special cruise.

“They wanted to get as many people to take that steamboat down to Mobile as possible,” Brown said.

The advertising may have worked too well, as the pilot of one particular voyage became concerned with the added weight and how difficult it was to steer the boat.

The worries seemed to stay with the pilot until, late one February night in 1858 as the vessel neared Naheola, a fire broke out on the steamboat.

With people panicking and the lifeboat inaccessible due to the flames, passengers began jumping from the boat, clinging to items thrown overboard first as a makeshift lifeboat or simply trying to swim ashore.

According to Brown, body counts varied widely. He said a newspaper at the time reported 65 deaths and that individual reports estimated the death count to be closer to 120.

In 1912, the mystery of the fire may have been laid to rest as a man in New York confessed to a priest that he and a friend planned to rob a rich planter on the steamboat that night and set fire to the man’s mattress as a diversion. From there, the fire spread.

“And that was a dying man’s confession so we’re not sure how true that is,” Brown said.

According to Brown, the ghost of the steamboat is still seen today.

“Every February, on the anniversary of the Elizabeth Battle Steamboat’s [sinking], people see the ghost ship,” he said.

Brown even mentioned that a student, who works at the Demopolis Lock and Dam, reported getting calls about a burning ship on the river on the anniversary of the sinking of the Eliza Battle Steamboat.

All stories featured in this article are in Brown’s book “The Haunting of Alabama,” published by Pelican Press. Brown has been researching ghosts for his books since 1996. He has also been actively hunting ghosts for the past 12 years.

(This article originally appeared in the Wednesday, October 31 issue of the Demopolis Times.)